Maintaining the reliability of power transmission infrastructure is critical for industrial operations and public livelihood. Foreign objects on high-voltage overhead lines, such as plastic bags or bird nests, pose significant risks of electrical faults. Traditional inspection methods require manual line walking or post-flight image screening—both labor-intensive and time-consuming. Surveying drones (UAVs) offer an efficient alternative but face limitations in real-time anomaly detection and autonomous navigation without expensive hardware upgrades. This work addresses these gaps by designing a lightweight external device that enables standard surveying UAVs to perform autonomous inspections with embedded real-time foreign object identification.

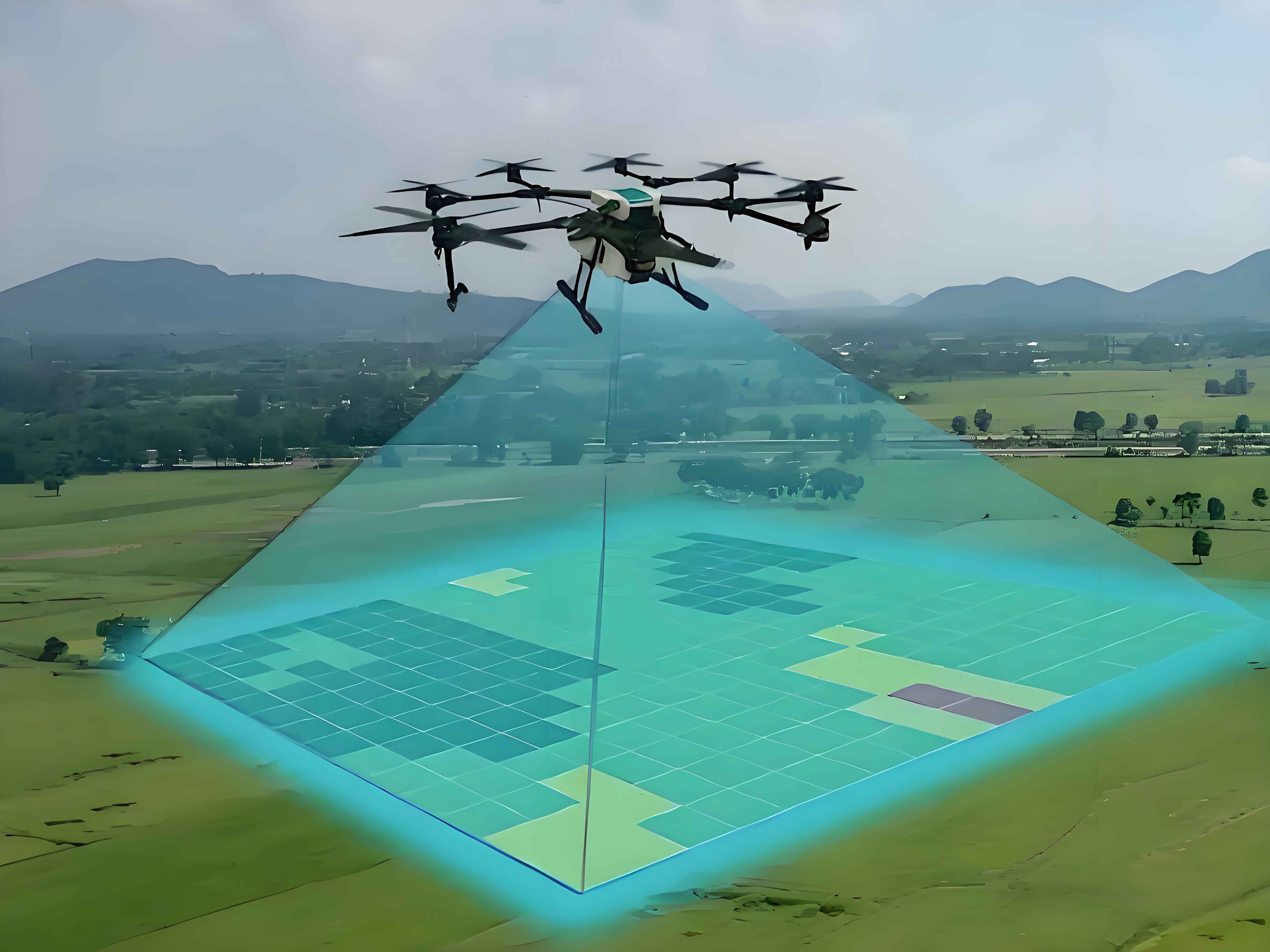

The system architecture integrates autonomous navigation, real-time image processing, and data classification. As shown in the functional flow below, the device imports predefined flight paths and reference images. During operation, it continuously monitors battery levels, executes autonomous routing, validates captured images against trained models, categorizes results, and transmits alerts. All computations occur onboard using a Raspberry Pi 4B microcomputer, minimizing dependency on ground stations.

| Module | Components | Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| Processing Core | Raspberry Pi 4B | Runs YOLOv5s inference, controls sensors |

| Positioning | AT6558 GNSS chip | Provides latitude, longitude, speed, heading |

| Communication | Type-C interface | Data/power transfer to UAV |

| Alert System | Programmable buzzer | Audible warnings for anomalies |

Hardware implementation emphasizes minimal weight (141g) and safety. The polyethylene enclosure attaches beneath the surveying drone via adjustable straps. Power and data exchange occur through a Type-C connector, leveraging the UAV’s battery without modifying internal circuits. Thermal management is achieved through an open-top design and passive cooling. Mounting flexibility allows integration of auxiliary sensors like thermal cameras.

Autonomous navigation uses GNSS data for real-time path correction. The device calculates deviations between planned and actual coordinates, generating steering commands. Positional accuracy follows the AT6558’s 2.5m CEP specification. Flight dynamics are governed by PID control:

$$ \Delta u(t) = K_p e(t) + K_i \int_0^t e(\tau) d\tau + K_d \frac{de(t)}{dt} $$

where \( \Delta u(t) \) represents the control output (throttle/pitch/yaw adjustments), \( e(t) \) is the positional error, and \( K_p \), \( K_i \), \( K_d \) are tuned gains. This enables centimeter-precision hovering during image capture.

Foreign object detection employs YOLOv5s for its optimal speed-accuracy tradeoff on edge devices. The model is trained on a custom dataset of 4,000 annotated images containing common line obstructions. Transfer learning starts from pretrained COCO weights, with hyperparameters configured as:

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Epochs | 100 | Training iterations |

| Batch Size | 4 | Limited by Pi’s RAM |

| Input Size | 640×640 | Image resolution |

| nc | 1 | Single-class (foreign objects) |

Training convergence is shown in the mAP and precision curves. After 100 epochs, precision stabilizes at 0.8, while mAP@0.5 reaches 0.5—sufficient for real-time alerts despite dataset limitations. The loss function combines localization, confidence, and classification terms:

$$ \mathcal{L} = \lambda_{\text{coord}} \sum_{i=0}^{S^2} \mathbb{I}_{ij}^{\text{obj}} \left[ (x_i – \hat{x}_i)^2 + (y_i – \hat{y}_i)^2 \right] + \lambda_{\text{coord}} \sum_{i=0}^{S^2} \mathbb{I}_{ij}^{\text{obj}} \left[ (\sqrt{w_i} – \sqrt{\hat{w}_i})^2 + (\sqrt{h_i} – \sqrt{\hat{h}_i})^2 \right] + \sum_{i=0}^{S^2} \mathbb{I}_{ij}^{\text{obj}} (C_i – \hat{C}_i)^2 + \lambda_{\text{noobj}} \sum_{i=0}^{S^2} \mathbb{I}_{ij}^{\text{noobj}} (C_i – \hat{C}_i)^2 + \sum_{i=0}^{S^2} \mathbb{I}_{i}^{\text{obj}} (p_i(c) – \hat{p}_i(c))^2 $$

where \( \mathbb{I}_{ij}^{\text{obj}} \) indicates object presence in grid cell \( i \) and anchor \( j \), \( (x,y,w,h) \) are bounding box coordinates, \( C \) is object confidence, and \( p(c) \) is class probability.

Field tests validated both navigation and detection modules. Autonomous routing trials used a DJI Mini 3 Pro surveying UAV covering 500m of simulated transmission lines. Path-tracking accuracy remained within ±3m despite wind interference, with 7% battery consumed over 2 minutes. For object recognition, black wires suspended plastic bags at 8m height. The surveying UAV identified anomalies at 30°–60° tilt angles and various altitudes (5–15m), achieving 12 FPS inference on Raspberry Pi. Environmental robustness was confirmed across lighting conditions (1,000–80,000 lux) and temperatures (15°C–31°C).

| Test | Condition | Result | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Navigation | 500m route, 5m/s wind | Completed in 120s | Positional error < 3m |

| Detection | Plastic bag @ 8m height | Real-time ID | 12 FPS, 78% precision |

| Environmental | 15°C–31°C, 5–80k lux | No image distortion | mAP@0.5 = 0.51 |

This work demonstrates a practical solution for automating high-voltage line inspections using accessible surveying drones. By offloading autonomous navigation and real-time object detection to an external module, the system eliminates post-flight image screening delays. The Type-C interface ensures compatibility with commercial UAVs without internal modifications. Future versions will integrate infrared sensors for thermal anomaly detection and expand the dataset to improve recognition accuracy for rare obstructions. The approach significantly lowers barriers to automated power infrastructure monitoring, particularly in resource-limited settings.